A few weeks ago I was asked to write a guest blog post for the CPED Blog – the post is cross-posted here. Big thanks to Caroline White and Mary Mathis Burnett for giving me feedback on early (and late) drafts.

A Reflection on Teaching in Online EdD Programs –

The CPED program design concepts state that mentoring and advising should be guided by: equity and justice, mutual respect, dynamic learning, flexibility, intellectual space, supportive learning environments, cohort and individualized attention, rigorous practices, and integration. For those of us that teach online EdD programs, the medium for this work consists of Zoom calls, text messages, telephone calls, email, Word or Google Docs, and a Learning Management System (LMS). As a clinical associate professor with the Leadership and Innovation EdD program at Arizona State University, this is territory I know all too well!

If you look up a definition of LMS, you will see that it is used for the “administration, documentation, tracking, reporting, and delivery of educational courses.” All of those actions are in opposition (at times) to the CPED design concepts. Doctoral coursework is not about tracking and automating learning. It is very understandable however that because our primary classroom environment is constructed for this purpose, our students may experience, or even expect rigid and inflexible experiences. We have to actively work against the “walls” of our virtual classrooms in LMSs to build friendly hallways for our online students.

The purpose of this post is to share a few tangible ways that we as faculty can be active conduits for our students in online spaces, and how we can push through the boundaries of our digital classrooms to create supportive learning environments.

Get to know your students & help them get to know each other

The computer screen is not a barrier to relationships – we just have to work in different ways to create meaningful bonds with each other. We are working with complex individuals, who are never just students and have competing priorities and demands on their time. The natural “hallway” moments that happen in-person classes are not as frequent, and potentially non-existent in online classrooms – so we have to work hard to provide this connection for them. The students have a desire to know each other, and, as faculty we can help support that need and continually think of ways to help our programs think about this for our entire student body.

A few weeks before the semester starts, I send out a “Getting to Know You” survey (via Google Form) to my students. I ask a few simple questions:

- How do you pronounce your name

- Preferred pronouns

- Profession

- Problem of practice in a sentence

- Location

- Is there anything we should know about your learning/work style so we can be more effective in providing you feedback and support this semester?

- Is there anything else you would like to ask, or would like us to know?

The answers to questions 6 and 7 are always extraordinarily helpful, and provide me with insights that would never come up in a “traditional” introductory discussion forum posts. As this practice has evolved, students have asked me if I could share the answers to questions 1-5 with each other. (Of course, why didn’t I think of this before!) Our students complete the program as a cohort. As an instructor, I initially assumed that they knew each other well, but quickly realized this was not a fair assumption.

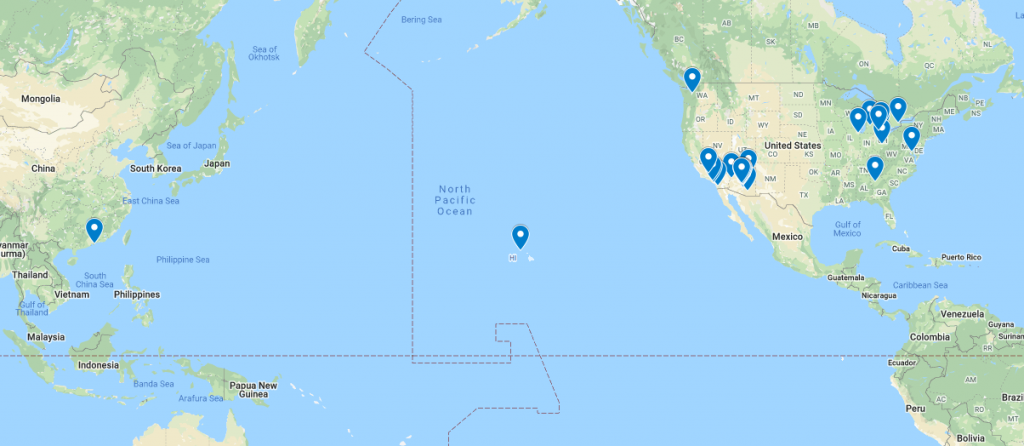

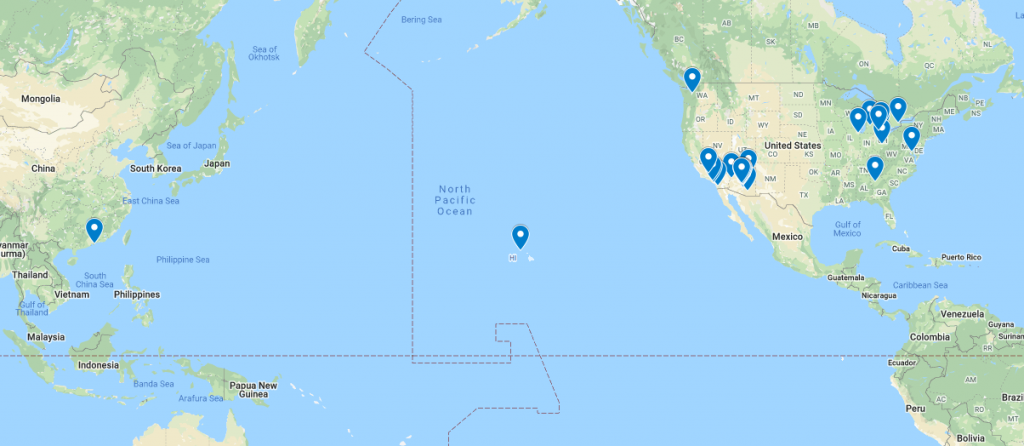

Another way to bring a sense of community and space from the survey results is to create a map. I do this by using the My Maps feature in Google Maps.

For privacy and security, I don’t list full names on the map, and I don’t make the map public. The visual alone is a powerful representation to show that a class is indeed spread across the world, and we have to be cognisant of the fact that it is not 11:59pm everywhere. (More thoughts on that here.) It also shows that I care where they are. Connections can’t be programmed into systems, we have to help make them happen.

Situate feedback as a conversation

I’m very intentionally using the word feedback instead of grading. I have found that there is a lot of negative educational baggage around being “graded.”

Our institution uses Canvas as an LMS. The gradebook in Canvas has a commenting feature and Google Docs allows threaded comments. However, in using these tools, I have found that I have to prompt students to respond to the comments. I think this has to do with the rigidity of the system, if it’s in an online gradebook, then, it feels “final.” Once they realize that I’m deeply invested in their work (literally at a line by line basis at times in a Google Doc) then, they start to see this as a supportive and individualized space to learn.

I have also experimented with verbal feedback. If your institution has Zoom cloud recording, this process is easy and accessible. Open up your personal meeting room, share your screen, record to the cloud and you’re good to go. A few minutes after you end the recording, you’ll get a link with the recording along with a transcript. Continually try to push against the boundaries of digital classroom spaces (specifically those built into LMSs) to build connections and conversations.

Be present

I am present with my students in their feedback, not only in comments, but, also in the timeliness of feedback. I make feedback a priority. If an assignment is due on one day, I set aside the next two days to give feedback. For longer assignments (e.g. dissertation proposal draft sections) it may take longer, but, I am sure to tell the students how long that will be.

Feedback is murky territory, and all too often I hear stories about feedback taking weeks (in both online and face to face classes). I think the distance is exacerbated if we are not intentional about our presence. When an assignment gets submitted into the digital ether, how is a student to know when (or if) it will come back? I am sympathetic to instructors, we have a lot of competing priorities and pressures. A way to manage frustration is to very simply tell students when feedback will be given. It does take time to provide feedback, especially when we have a full caseload of classes, the simple act of knowing and managing expectations goes a long way.

This beautiful article by Rose & Adams (2014) should resonate with both faculty and students. Being present can take many shapes and forms. For me, it comes via weekly videos, a practice that I have been embedding in online courses for quite a while. Our courses are delivered via weekly modules, and, are primarily text based. The videos are my way of checking in and walking with the students through the weekly modules or highlighting spots that may be challenging. To facilitate the weekly recording, I use Zoom Cloud Recording. You could also use SnagIt, or other screen capture tools and upload to YouTube (which provides automatic captioning) or a video hosting tool at your institution.

Keep learning

I have been learning and teaching online since 2000 (in 2020, it feels a bit historic to type that out.) Twenty years into this, I still have a lot to learn. I build in time for reflection on my own blog, I talk with my students, and I talk with others at conferences. I engage in conversations in digital spaces like Slack, Twitter – and I’m always thinking of how to leverage these spaces to build conduits for and between our students. The journey of improving and understanding my critical digital pedagogy (Morris & Stommel, 2018) will never end.

I would like to end this post with an invitation – for further discussion in the comments, or on Twitter (the hashtags #HumanizeOL, #EdDChat, #CPED are great places to congregate) or for collaboration on research. Fully online doctoral programs are a tiny slice of the learning landscape, collectively, we could work to share practices and pedagogy to humanize the experience for all.

References

Adams, C., & Rose, E. (2014). “Will I ever connect with the students?” Online teaching and the pedagogy of care. Phenomenology & Practice, 8(1), 5-16.

Morris, S.M & Stommel, J. (2018) An Urgency of Teachers: the Work of Critical Digital Pedagogy https://urgencyofteachers.com/

Leigh Graves Wolf is teacher-scholar and a Clinical Associate Professor in the Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College at Arizona State University. Leigh teaches with the Educational Leadership and Innovation EdD program and is a faculty fellow with the Office of Scholarship & Innovation. Her work centers around online education, K12 teacher professional development and relationships mediated by and with technology. She has worked across the educational spectrum from K12 to Higher to further and lifelong. She believes passionately in collaboration and community. Leigh shares all of her work and ideas publicly on her blog, twitter, & flickr.

Leigh Graves Wolf is teacher-scholar and a Clinical Associate Professor in the Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College at Arizona State University. Leigh teaches with the Educational Leadership and Innovation EdD program and is a faculty fellow with the Office of Scholarship & Innovation. Her work centers around online education, K12 teacher professional development and relationships mediated by and with technology. She has worked across the educational spectrum from K12 to Higher to further and lifelong. She believes passionately in collaboration and community. Leigh shares all of her work and ideas publicly on her blog, twitter, & flickr.